I ran across kekri once again as I looked for a theme for this week’s Keskustelutunti (Finnish Conversation Hour). I had first encountered kekri when visiting museums in Finland and reading a few books, but had never really looked into it further than the passing mention. What I discovered was something I think I have been longing to know about for a long time.

Basic information about kekri

Kekri is a Finnish harvest festival. When all of the work is done gathering the potatoes, grains, and slaughtering some of the livestock to help bring us through the winter months with enough resources, kekri celebrates the completion of this hard, yet necessary work. Since kekri was based on work that needed to be done according to how the growing and harvest seasons went, there is no fixed date for the celebration and in fact, the kekri festivities took place over many days. That being said, kekri usually took place sometime between September 29th (Mikkelinpäivä or Michaelmas) and November 4th (Pyhäinpäivä or All Saints Day in Finland).

Before Finland and most of the Western world joined the 12-month calendar system, kekri was actually considered to be the end of the year. It makes sense - when the majority of the agrarian work was completed, workers could rest and that was something to celebrate! Since this was seen as the end of the year, there were traditions that ended up translating to Christmas traditions, once the calendar was revised. For example, two figures - Kekripukki and Köyritär - would visit the various homes in a village and would require good hospitality or they would threaten to break the homeowner’s oven. Back in the day, the oven and the home’s heating system were one in the same, so to have a broken oven would mean no heat for the winter, a most unwelcome situation. Let’s just say Kekripukki and Köyritär never went hungry or thirsty throughout their visit around the village. Kekripukki, many see, as a direct relative to today’s Joulupukki (Finnish Santa Claus). Perhaps that is why Santa actually still comes in the flesh to visit the homes of Finns and always gets offered cookies, coffee, or other treat, although Joulupukki has dropped the whole ‘threatening to break your oven’ routine of his cousins, Kekripukki and Köyritär, and instead brings gifts.

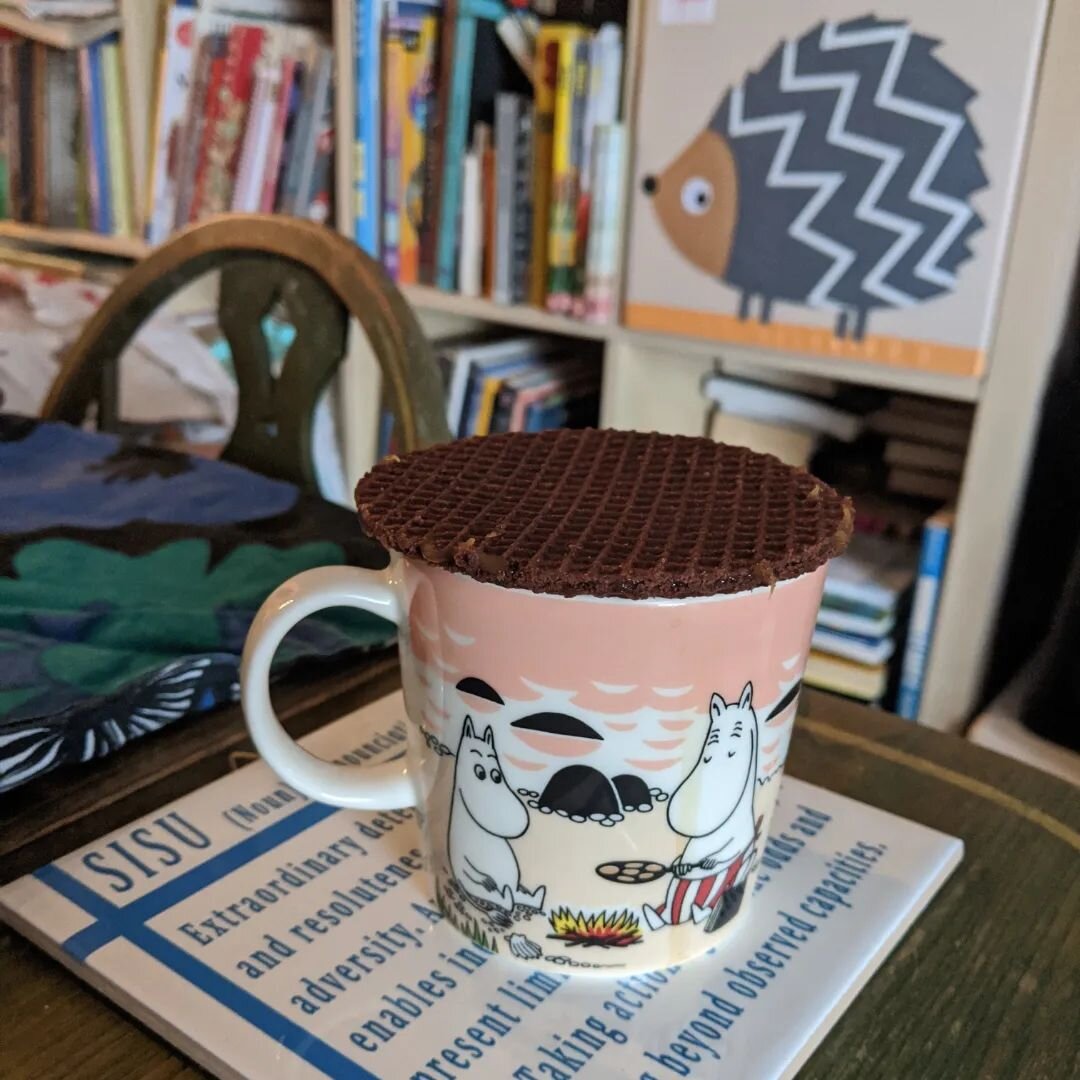

Since kekri happens at the end of the harvest season, there was plenty of food on hand for guests like Kekripukki, Köyritär and any other members of the community. In fact, people were expected to eat plentifully, otherwise, it could bode ill for the coming harvest season next year. Meat, grains, and spirits were consumed in abundence. Grains were exceptionally important to the farmers during this time. The first bread for the winter was made during kekri at the fall equinox during the full moon and is called kylvöleipä (sowing bread). Grain dolls were also created during this time and placed at the table. Turnips are also a very special food during kekri. They were grown via slash and burn in eastern Finland and in peat bogs in Western Finland. Turnips were harvested multiple times a year, but prior to kekri they were harvested for consumption into the early winter.

Village rules and codes of conduct were also more relaxed during this time. Villagers were allowed to play games, tell stories, and practice magic. Ancestors were believed to move more freely during kekri and they would come to check on the family farm and also would require hospitality. Sauna was heated for them, while food was prepared to offer them. Bonfires were lit to keep the restless souls away and families would carve turnip lanterns.

Why does kekri mean something to me?

Kekri also serves as a time for reflection and honoring one’s ancestors. My Finnish biological roots were from far Eastern Finland and Karelia. We still have second cousins in that area and we visited them on my first trip to Finland. Our Finnish family history is a tragic one, familiar to an unlucky few whose families experienced similar ideological tragedy.

I recently started doing more research into my Great Grandma’s sister (Kerttu) who moved with her parents as Soviet Pioneers from the US where the two girls were born to the wilds of Karelia to help establish some kind of ‘workers’ paradise’ there. When consulting photos I had of the few things Kerttu left in the US with her sister (my Great Grandma Irma) when she returned to the Soviet Union after visiting in the 80s, I found an address and harnessed the power of GoogleMaps to find out exactly where she used to live in Karelia. This was actually kind of challenging because I had to translate the Finnish on the address note to Russian and then search the streets of Petrozavodsk to find the exact address listed. I am still not sure if that buiding is the same one as when she lived there until the 80s, but I have a sense maybe not so much has changed there as typically had here in Minnesota since that time, including architecture.

This research has given me a lot to think about. I am not sure if I will ever make it to Karelia where my Great Great Grandma (Kerttu’s mother) labored to her death and was buried in a mass grave, but I have appreciated getting to know more about how life was for Kerttu and her parents via Google Map’s Street View and research done in Finnish via a variety of Karelian cultural and history sites.

Kekri gives me a time to reflect on my Finnish and other family history, including that of the tragedy of my Great Grandma’s nuclear family members. I will share more about this research and family history in later blog posts. There is definitely a lot more for me to learn about my family, their tragedies, and their survivalism. I look forward to dedicating time this winter to discovering more.

Where else can I learn about kekri and its traditions?

Talonpoikaiskulttuurisäätiö (Farmer Culture Foundation) has put together a very wonderful site all about kekri. Although this site is mostly in Finnish, a video and a few pages also have some information in English, for wider access. I especially recommend watching this video for an overview of kekri and how it is related to other celebrations around the world (Finnish - English).

The University of Jyväskylä has put together a good info page in English about kekri’s crops and other traditions leading up to joulu (Christmas).

Kekri in a nut shell is a time for celebration, rest, reflection, and honoring one’s ancestors. How will you celebrate kekri?