Achieved “family” members Jorma and Leena in front of their home in a suburb of Oulu, Finland

It seems to me that nearly everything in America becomes some kind of competition. This can be frustrating if, for example, someone is leaning on a factor out of their control in order to prove something about themselves in comparison to another person.

Learning about Sociology, Anthropology, Scandinavian Studies, and Spanish during my Gustavus years

I remember learning in my college Introduction to Sociology course that there is a theory of two kinds of statuses: ascribed and achieved. These terms were coined by Ralph Linton, an American Anthropologist in The Study of Man (1936):

Ascribed status is a status that you are born with or involuntarily assumed later on in life. It is “often based on biological factors that cannot be changed through individual effort or achievement.” Several examples of ascribed status include: age, birth order, caste position, daughter or son, ethnicity, and inherited wealth.

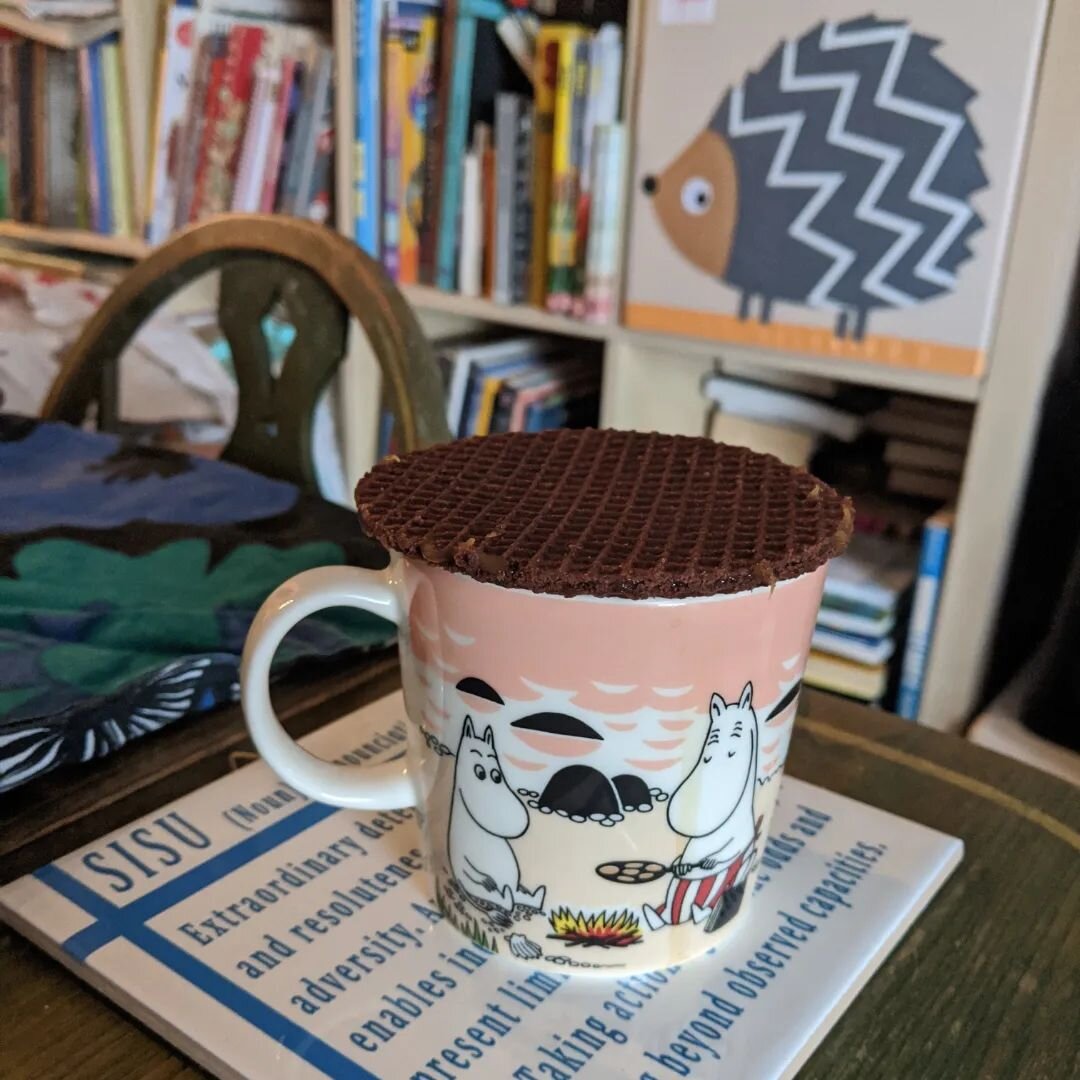

Achieved status, on the other hand, is earned and chosen. It is a status based on “personal accomplishment and merit, that serves as a reflection of ability, choice, or personal effort.” Examples of achieved status are: education, marriage status, and occupation. If a certain language (like Finnish or English) was not spoken to you when you were growing up, then your ability to speak that particular language must be an achieved status. You must have worked at it and it was (at least partially) a choice.

Ethnic groups in America and elsewhere have been comparing their ethnic gene pool for centuries, but for what? We don’t have a monarchy here, where a direct descendant of the royal family assumes the throne to lead the less or non-royal groups, so why do we care so much about what percentage we are of this, that, or the other thing?

As our scientific technology improves and DNA was discovered in the mid-19th century and structure was figured out in the mid-20th century, we have been fascinated by what we are made of and the impact that has on our individual and collective lives. When DNA testing was available to the general consumer, many families who had been using their ascribed DNA statuses saw this as an opportunity to get tested to find out and prove how (insert any ethnicity here) they are, while others decided it was safer to just rely on the family narratives they had been told. Some of the people tested had surprises come up in their data. *Wait, we are related to him? Huh? I thought we were 100% Finnish -- that isn’t what grandpa told us?!* While others had the data validate their ethnicity. For years there has been a flood of announcements on Finnish and other heritage boards on Facebook and other social media proclaiming that, indeed, the individual posting the comments is 100% Finnish and how proud they are.

As someone who knows without doing the DNA test that I am nowhere near 100% of any of a number of ethnicities (German, Dutch, French Candadian, and certainly Finnish), I find the testing being used to prove that someone is 100% of anything kind of frustrating. Perhaps I am jealous that I can’t play the game? All I know is that some of the most Finnish people I know have absolutely no Finnish DNA in them. When qualifications for Finnishness are based on only DNA, you are left with a nearly disparate lot of people around the world. When you instead choose to evaluate Finnishness based on other factors, beyond ascribed status factors, then you can expand the community. If instead Finnishness was based on language, cultural practices, or other decision-based achieved statuses, the numbers game rhetoric would not be as prominent and we could have a few more winners.

Achieved “family” members Kari and Anneli in front of their home in a suburb of Oulu Finland

One cannot compete fairly with ascribed status, only ascribed. So the next time you plan to win an argument by relaying how “Finnish” you are, think about Linton and his theory and ask: Is my authority coming from a place of achieved status and resulting knowledge or am I simply leaning on mating decisions made by my ancestors?

—Elizabeth “Helvi” Brauer

@luumuabc

@luumu_living

@luumu_suomen_kieli

luumuabc@gmail.com

Resources and further reading: